As explained, Poe saw beauty through death, and subsequently death through beauty. He was often moved by woman’s beauty, to the point, as the previous quote infers, to tears. From what we can ascertain, Poe found love for the women he admired not only through their physical beauty, which we will provide description examples of below, but also through their ability to inspire his writing. And perhaps we may receive a glimpse of the beauty that so moved Poe.

Jane Stanard

Jane Stanard was the mother of Poe’s childhood friend, Robert Craig Stanard. Poe would often visit Robert just to be able to spend time with Jane, whom he’d developed boyish feelings for. She treated him like a son and provided him with the maternal love that he craved, not to mention that she was described as being “a woman of great beauty and of a somewhat classic countenance…Her family and relatives have preserved into modern times the memory of one unusual for her warmth of heart and graciousness in an age of gracious manners. In short, Mrs. Stanard is known to have been a beautiful woman, a splendid hostess, and possessed of a peculiarly radiant and extraordinary and memorable personality”(Allen 88).

Not only did Poe find, according to Hervey Allen, “the chivalrous ideal of a young boy’s first idolatry and the material comfort of sympathy and appreciation,” but he also found arguably his first muse. Stanard, if at all known, is recognized as being the inspiration of Poe’s poem “To Helen.” The passion Poe expressed at such a young age indicates that not only did he appreciate the outward beauty of women, but as indicative of Stanard’s personality and his poem dedicated to her, he found a familial and transcendent love. He placed his “Helen” on the pedestal that Helen of Troy would have been placed upon, and he raised her image above his eye to admire from afar, despite being so close.

Her death in April, 1824 marked a difficult time in Edgar’s life, and, according to Allen, “There is an immortal story that Poe haunted the spot” (90). There is no doubt that many may have heard this tale, and, yes, it is widely told that Poe and Robert would often visit Jane’s grave to morn and weep-Robert, for his mother and also perhaps mentor and great friend, and Poe, for his first love, his “Helen,” and one of, if not his first, ideal forms of beauty.

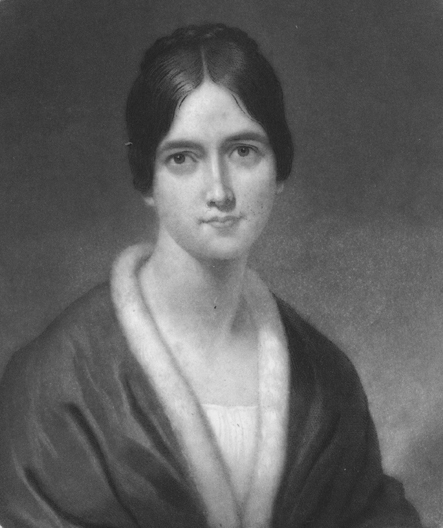

Elmira Royster

When Poe was just sixteen, he met his first fiancée, Sarah Elmira Royster. She would also become his last fiancée and love before his death in 1849. According to Poe biographer Hervey Allen, “…she was about fifteen and dowered with a trim little figure, an appealing mouth, large black eyes, and long, dark chestnut hair” (110). We emphasize that this was when Edgar first came to know her, amidst the beauty of childhood bliss and blooming love that happens at that tender age. She would have been the second significant female figure in his life to romantically interest him, and we see, from this description, that she held the characteristic dark eyes and hair that may have made her appear pale in complexion-at least, to Poe and his romantic eye.

Forged Drawing of Young Elmira Royster

As many may know the tale, Poe went off to college, Elmira’s father destroyed all of the letters that Edgar sent to her, and she became engaged to Alexander Shelton. When Poe returned, he learned of the unfortunate fate that had befallen their love, thus inspiring of a few of his poems including “I Saw Thee On Thy Bridal Day….” and “To [Elmira],” which even alludes to her eyes, “in Heaven of heart enshrined,” falling unto his “funereal mind,” thus displaying the connection of beauty with death.

Not only do we have a copy drawing of a portrait of Elmira sketched by Poe here at the museum, which showcases her beauty and allows us to see the beauty Poe saw in her, but we also have other numerous quotes regarding her appearance later in life. You can read more about Elmira and her character and appearance in the post for this month’s “Museum Object of the Month,” here.

Virginia Poe

Many are familiar with Virginia Poe, for she was the youthful wife of Edgar Poe. It may be argued that she was the main inspiration for many of his works, including “Annabel Lee,” “Ulalume,” and “Eleonora.” In the following passages, we receive a glimpse of her outward appearance.

“She was rather small for her age, ‘pump, pretty, but not especially so, with sweet and gentle manners and the simplicity of a child,'” she was described as being during the year of 1835, when she and Poe married. It was also said, according to Hervey Allen, that “When she [Virginia] was twenty-odd it was noticed by competent persons that she did not appear to be over fifteen. Her mind developed more normally that her cousin’s [Rosalie Poe], but her body was never wholly mature…it was remarked that the otherwise childish prettiness of Virginia was marred by a chalky-white complexion…” (311-312).

According to Allen, in accordance with Poe’s statement initially quoted at the beginning of this post, “For Poe the ‘delicacy’ which the advancing stages of the dread, but then fashionable and romantic, disease, conferred on his wife-the strange, chalky pallor tinged with a faint febrile rouge, the large, haunted liquid eyes-gradually acquired a peculiar fascination” (312). Although this is simply painted by Allen, who would not have seen Virginia personally during her decline before her death, his description is certainly romantic and promotes the ideal beauty of death to Poe.

Finally, “Mrs. Poe looked very young; she had large black eyes, and a pearly whiteness of complexion, which was a perfect pallor. Her pale face, her brilliant eyes, and her raven hair gave her an unearthly look. One felt that she was almost a disrobed spirit, and when she coughed it was made certain that she was rapidly passing away” (Mrs. Mary Gove Nichols, “Reminiscences of Edgar Allan Poe,” reprint, p. 8).

Concluding this section with Virginia, we can see that she most resembles the ideal figure of beauty quoted by Poe-she may have perhaps even influenced Poe’s famous quote, as she would have been the closest embodiment of death while he remained by her side until her finale repose.

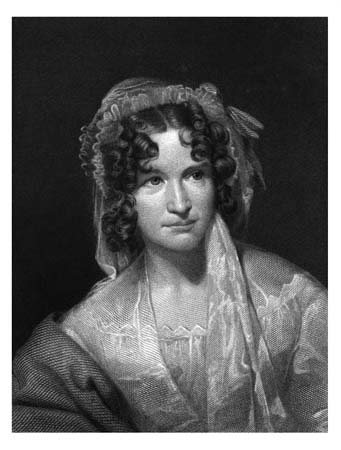

Frances Osgood

Frances Osgood was notorious for arresting Poe with her lucid gaze and poise, not to mention the secretive romantic poems that she exchanged with him, albeit publicly. In the following descriptions, however, not only will we see Frances’ outer beauty, but also the inward beauty she held.

In character she is ardent, sensitive, impulsive-the very soul of truth and honor; a worshipper of the beautiful, with a heart so radically artless as to seem abundant in art; unusually admired, respected and beloved. In person she is about the medium height, slender even to fragility, graceful whether in action or repose; complexion usually pale, hair black and glossy; eyes a clear, luminous grey, large, and with singular capacity for expression (Poe 129, Godey’s Lady’s Book).

In the poem, “Stanzas [To F.S.O],” Poe writes, “The gladness of a pure heart/ Pure as the wishes breathed in prayer…/ The fullness of a cultured mind, Stored with the wealth of bard and sage…/ The grandeur of a guileless soul, / With wisdom, virtue feeling fraught, / Gliding serenely to its goal, / Beneath the eternal sky of Thought:- / These should be thine…” (Mabbott 386)

Poe comments on the purity of her heart and her “cultured mind,” almost proving that she has a transcended beauty about her. She, without question, inspired many other poems, which Poe dedicated to her, including “A Valentine.”

Sarah Helen Whitman:

Finally, Whitman can be considered as one of the more eccentric love interests of Poe. This maiden of the occult cast her spell on Poe, bewitching him with only her vague figure from afar.

Below is the following account of when Poe first saw the spectral poetess.

“At a late hour, however, on this summer night, Poe became restless and left the hotel. He strolled past Mrs. Whitman’s house at the corner of Benefit and Church Streets. There was moonlight, and Mrs. Whitman happened to be standing in the street door taking the air” (Allen 528).

Our next piece of evidence lies in the lines of Poe’s poem, “To Helen,” written solely for Whitman.

“To Helen”

I saw thee once-once only-years ago:

I must not say how many-but not many.

It was a July midnight; and from out

A full-orbed moon, that, like thine own soul, soaring,

Sought a precipitate pathway up through heaven,

There fell a silvery-silken veil of light,

With quietude, and sultriness, and slumber,

Upon the upturn’d faces of a thousand

Roses that grew in an enchanted garden,

Where no wind dared to stir, unless on tiptoe-

Fell on the upturn’d faces of these roses

That gave out, in return for the love-light,

Their odorous souls in an ecstatic death-

Fell on the upturn’d faces of these roses

That smiled and died in this parterre, enchanted

By thee, and by the poetry of thy presence.

Clad all in white, upon a violet bank

I saw thee half reclining; while the moon

Fell on the upturn’d faces of the roses,

And on thine own, upturn’d -alas, in sorrow! (Mabbott 445)

Throughout this lengthy poem, Poe alludes to her eyes,

…the divine light in thine eyes-

Save but the soul in thine uplifted eyes.

I saw but them-they were the world to me.

I saw but them-saw only them for hours-

Saw only them until the moon went down.

What wild heart-histories seemed to lie unwritten

Upon those crystalline, celestial spheres!

How dark a wo! yet how sublime a hope!

How silently serene a sea of pride!

How daring an ambition! yet how deep-

How fathomless a capacity for love!” (446).

The ethereal and “divine” qualities of Whitman-almost spiritual qualities-seemed to have invoked in Poe a mature form of love.

Although Poe saw his Helen “once-once only years ago,” according to this poem, he and the poet continued to keep in touch through numerous letters thereafter, which display their evolving love for one another. They would eventually meet again in person and, that same night, Poe would propose to her in a graveyard. This impulsive gesture showcases the themes of death and beauty and love colliding through the morbid act. Although she did not agree initially, she finally accepted Poe’s proposal at a later date; however, their marriage would be called off for numerous reasons.

As we have gathered insight into these five individual women who influenced Poe not only through their beauty but also through their character, we also see that they influenced his writing. The writings chosen for most of these women seem to have an air of melancholy about them, thus proving that although their beauty and muse could bring him happiness, loving a woman could also bring despair, whether it be through the literal deaths of his wife and first love, or the figurative deaths of his other relationships. It should come as no surprise then that Poe felt that “[a] certain taint of sadness is inseparably connected with all the higher manifestations of true Beauty” (The Poetic Principle).

> Donate

> Donate